On Monday night, a three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit struck a blow to President Barack Obama’s attempt to confer lawful presence and work authorizations on more than four million illegal immigrants.

In a 2-1 decision, the panel ruled that a preliminary injunction that blocks Obama’s “Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents” (DAPA) from going into effect must stand.

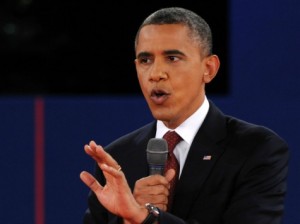

Obama’s Executive Action on Immigration

After Congress refused to pass the DREAM Act at least two dozen times between 2006 and 2011, Obama decided to bypass Congress altogether and “change” the law by executive fiat.

The administration also created DAPA, conferring deferred action on illegal aliens whose children are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents, provided no other factors make deferred action inappropriate. In addition to lawful presence, DAPA grants deferred-action recipients benefits such as work authorizations, driver’s licenses, Social Security, and other government benefits, costing an estimated $324 million over the next three years, according to the district court.

Texas and 25 other states challenged DAPA, alleging that it violates the Constitution’s Take Care Clause and the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). A federal district court held that DAPA violated the APA’s notice-and-comment requirements and preliminarily stopped the Department of Homeland Security from implementing “any and all aspects or phases” of DAPA. Earlier this year, the Fifth Circuit denied the United States’ request for an emergency stay.

Court Finds States Can Sue Obama Administration Over Immigration Action

On Monday, the appeals court upheld the district court’s preliminary injunction, finding that Texas has standing to sue, and the states established a substantial likelihood of success on their claims that DAPA violated the APA. The court did not rule on the constitutional issue.

The court found that Texas has standing to sue—meaning it has an injury that is “fairly traceable” to DAPA—because DAPA would enable at least 500,000 illegal aliens to receive subsidized Texas driver’s licenses, at a cost of $130.89 per license, which would end up costing the state millions of dollars. While the administration asserted that DAPA beneficiaries would then generate income for Texas by registering their cars and buying car insurance, the panel refused to accept this because “[w]eighing those costs and benefits is precisely the type of ‘accounting exercise,’ in which we cannot engage.”

The administration also argued that Texas could change its laws to avoid paying for the licenses. The panel noted:

[T]reating the availability of changing state law as a bar to standing would deprive states of judicial recourse for many bona fide harms[.] … [S]tates could offset almost any financial loss by raising taxes or fees. The existence of that alternative does not mean they lack standing.

Scrutinizing the Obama Administration’s Other Claims

The administration also argued that DAPA is simply an exercise of the president’s power of prosecutorial discretion, which is unreviewable by courts. While federal prosecutors are not required to enforce every federal law against every offender, prosecutorial discretion would be the exception that subsumes the rule if it could be used to suspend the application of laws to an entire category of clear offenders. As the panel pointed out, “although prosecutorial discretion is broad, it is not ‘unfettered.’”

Declining to prosecute offenders “does not transform presence deemed unlawful by Congress into lawful presence and confer eligibility for otherwise unavailable benefits based on that change.” Thus, the administration could not evade review by claiming that this deferred action was an exercise of prosecutorial discretion. The panel concluded that it is “much more than nonenforcement: It would affirmatively confer ‘lawful presence’ and associated benefits on a class of unlawfully present aliens. Though revocable, that change in designation would trigger (as we have already explained) eligibility for federal benefits.”

The administration further claimed that DAPA is exempt from the APA (which requires new or changed substantive rules promulgated by administrative agencies to go through a public notice-and-comment period) because it is a “policy statement” rather than a substantive rule. The notice-and-comment process helps ensure that parties that will be affected for a new agency rule “have an opportunity to participate in and influence agency decision making.”

The panel disagreed that DAPA is exempt from the APA:

At its core, this case is about the Secretary’s decision to change the immigration classification of millions of illegal aliens on a class-wide basis. The states properly maintain that DAPA’s grant of lawful presence and accompanying eligibility for benefits is a substantive rule that must go through notice and comment, but it imposes substantial costs on them, and that DAPA is substantively contrary to law.

The states won this battle in the immigration wars with the administration. At least for now, the administration is enjoined from implementing DAPA.

But this is likely not the last word on this case. The administration has announced it will ask the Supreme Court to review the Fifth Circuit’s decision. If the justices decide to take up the case, they could hear oral argument in early spring and issue a decision by the end of June.